From the introduction to Come As You Are: The Surprising New Science that Will Transform Your Sex Life:

And finally, in Chapter 9, I describe the single most important thing you can do to improve your sex life. But I’ll give it away right now: It turns out what matters most is not the parts you ar…

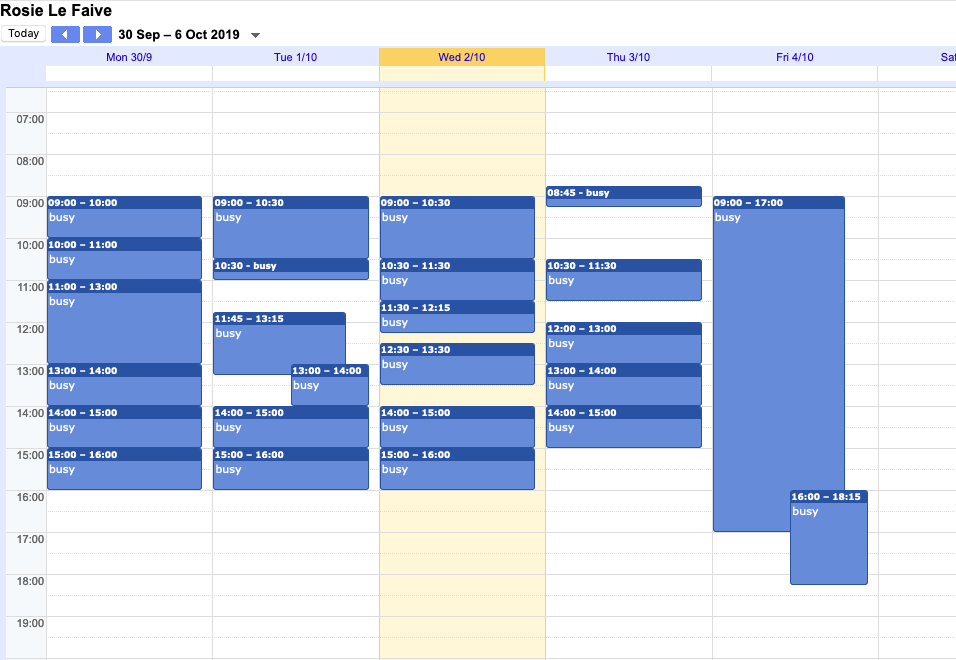

Month: October 2019

Dark matter permeates the universe. In fact it does more than permeate. It is the universe. 85% percent of everything that exists is actually dark matter. We can’t detect it, we can’t see it. But it’s there. In fact, the universe that we actually perceive, what you and I are made of, is the so-calle…

A short talk on Digital Literacy

I gave a very short talk today. I was invited to be part of a panel, that was one of the (many interesting) events in the Applied Geospatial Research in Public Policy (AGRiPP) workshop. Our topic was Digital Literacy / Digital Humanities. Each of my co-panelists and I had 5 minutes, so I said something kind of like this.

I’m Rosie Le Faive, and I’m a librarian, so my exposure to digital literacy is usually in the context of “information literacy” – delivering 50-minute lectures to first-year university students on how to use the library. And most of what I cover is how to use our databases to find peer-reviewed research, but every year when I get these classes, I like to think about how I can take it deeper. What does information literacy mean?

I’m going to go on a sidebar… forgive me, it will spoil a movie from 18 months ago… but it will tie back in. [CW: abuse, murder].

In Avengers: Infinity War, the character Gamora is murdered by her abusive father, and in the film it’s framed as proving his love for her [ick face]. Some scenes later, in the middle of a battle, Gamora’s boyfriend realizes she didn’t return and demands “Where… is… Gamora?”. Iron Man, (who’d never met them till this movie) counters with “I’ll do you one better… Who’s Gamora?” and Drax, who usually misses emotional tones of things, says “I’ll do you one better… why is Gamora?” The audience laughs, Drax is stupid, the question is silly.

But I really like his question. Why is Gamora? In this movie, her entire story arc exists so that she can die, and spur a man into action (or mis-action). This is a trope in media that’s known as fridging, after a brutal scene in a Green Lantern comic. Women characters biting the dust in order to further a man’s storyline is so popular that feminists have given it a name and are aware of it. Fridging doesn’t happen by accident. There were thousands of people involved in the making of this film. Why did this get through the layers of decision-making? Were there no women in the right rooms?

Why does this information exist? That’s the question that interests me. Why was it made, and what was its path from creation to distribution to wherever I encounter it? What structures and institutions were part of the story of this information, and what does it say about them?

A digital humanities project that I just became aware of, and deeply admire for its work in this, is Lily Cho’s Mass Capture project. It digitizes a collection of certificates – known as C.I. 9‘s, which Canada used to keep track of and control people from China. This was in the days of the Chinese “Head Tax”, and if someone from China living in Canada wanted to return to their home country and be able to return (without re-paying the head tax) they had to fill out a C.I. 9. It contained a lot of personal information – name, birthdate, where they’re from, identifying features, and photographs. This was particularly exciting [edit: that is the wrong word, maybe interesting or fascinating; left for accountability] because it was the first mass photography project implemented by the Canadian State. But Cho’s work explores how this bureaucracy creates and constructs people as “non-citizens,” a special kind of subject (in the Foucauldian sense) as defined by government policies founded in racism and white supremacy.

So I like to think about information literacy as knowing where to look for information (e.g. libraries!), and understanding who created that information – the direct provenance and responsibility, but also why is this information – what systems and structures and institutions brought it to me, and why did they consider it valuable?

Understanding these structures won’t let us be free of them. After all, “We live in a society.” But I find that awareness gives us context, and with the ability to reframe, more agency in how we construct stories.

Conservative Party candidate Robert Campbell, in The Guardian/UPEISU debate on Tuesday:

I’ve been talking to students. You talk to these young ladies right over here that I talked to last week. And the young lady is, I think is, from Egypt. And she told me what was going on.

So do I believe this l…

Pomodoro

Like others coping with adult ADHD (see also Leigh’s post and this article) I find it exceptionally hard to manage time. I’ve tried so many systems, and I have piles of lists and bullet journals that I’ve abandoned. But one thing I keep coming back to is “the pomodoro method“.

Super simply, it goes like this: Set a time for 25 minutes. During which, do the thing. When the timer dings, stop.

There’s a super-system where you take 5-minute breaks between repeated sessions and a longer break after four or something, but who has that kind of time?

I think there are a few reasons that this works for me. One – at any given time, I’m usually stressed about 3-7 large-scale items that need deep, creative attention, which could each eat up as much time as I can give them, all must get done but not super urgently, and are most likely to get pushed to the side in favour of answering random emails. I get stuck, because no matter what I choose, I can argue that I’m making the wrong choice. But 20 minutes won’t hurt anyone, so I can take that time and focus on something that I want to give my full attention to, stress-free.

Second – It’s long enough that I can actually focus and do the thing. And it seems to be about the right time where after the 25 minutes, a break actually helps because it lets me step back right before I get stuck down a rabbit hole, see the big picture, and often reframe my goals.

Third – and this is the most important, it does not require constant compliance. So many systems promise to organize your life – but you have to stick with them religiously. Some day I’ll write about my relationship with my bullet journal (and how it became abusive). I could go into how productivity methods echo Foucauldian disciplinary penal structures, with regimes that require you to always be producing! Highly structured! Schedules! But the pomodoro doesn’t care. You can come back to the pomodoro whenever you want, without punishment. It’s a good friend like that. It’s also indifferent to whether you actually “finished the thing” or how many things got finished. Who does the cult of productivity really serve? (Our capitalist masters is who.) And regardless, it gives a reasonably attainable feeling of accomplishment and satisfaction.

Speaking of capitalism (and hah I am in no way sponsored by this but)… I want to voice my appreciation for OXO Good Grips and their accessible design. I have a few of their kitchen gadgets, and they’re easy on the hands. I’m not sure if their “Triple Timer” was intended for physical ease of use, or for the time-blind like me, but having three pre-set countdowns, plus a desk clock is a huge help. Sometimes it’s worth having a dedicated device, because I can never find the beeping tab among my 48 open, and I can’t start a timer on my phone without answering 3 different messages and checking social apps.